DeFINitely Hot: Bye Bye Sharky - On the Shark Cage Diving Ban in NZ

2

It was early September, when the message came through that shark cage diving is now an illegal practice in New Zealand, decided by the Supreme Court supporting local paua (abalone) divers who have raised concerns about these ventures for several years now. The feud between the shark diving industry and the local fishermen at the Southern tip of NZ, Stewart Island, had already been simmering when I first came to NZ in 2013. Whether humans are at greater risk is a critical management objective as local communities acting as stakeholders may have mixed feelings about the establishment of cage diving operations in their region. In NZ, cage diving with great white sharks was established in 2008 around Stewart Island, South Island. Special concern was raised by the local paua diver community which felt restricted and at risk through the attraction of white sharks to the area.

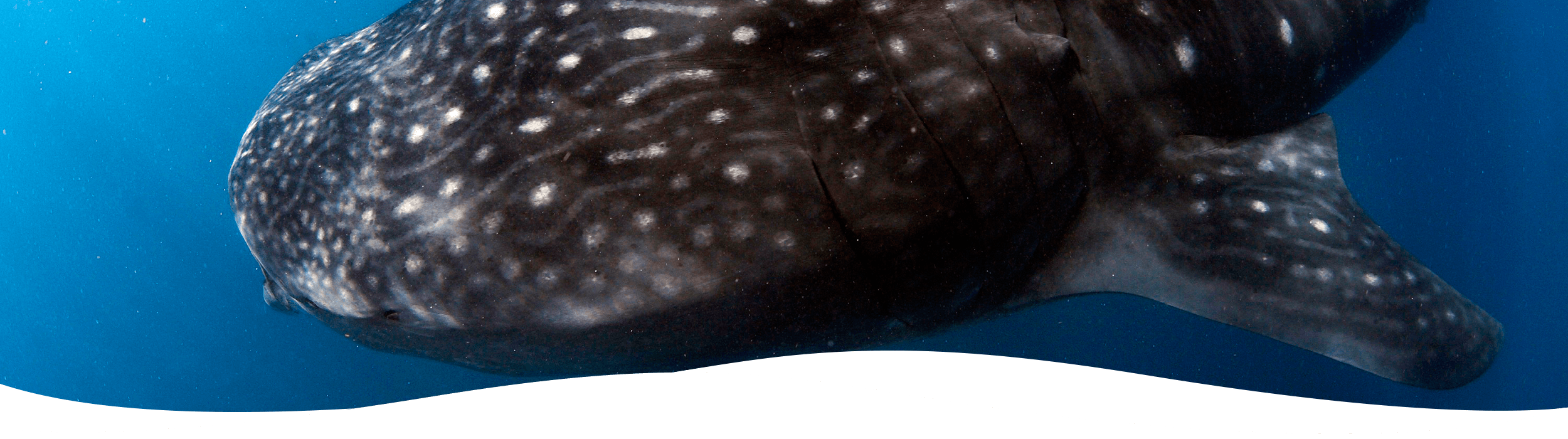

Shark cage diving is an activity where divers can observe large predatory sharks underwater within the safety of a shark proof cage, particularly in destinations such as South Africa, Guadeloupe (Mexico) and Adelaide (Australia). Target species are mainly great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), however, for bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) this method of observation is used as well. Cages are usually not entirely closed as they have a bigger gap in between to enable the shark tourist a better view on the animals. For this and for shark feeding, sharks must be attracted first. Unlike provisioning, cage diving operators are not feeding the animals but attract them with pieces of bait or the application of chum. Cage diving takes an important role in assisting conservation efforts of the great white shark via three mechanisms such as contributions to economic generation, education and integration as well as contributions to scientific research.

One of the main aims was breaking down the ‘Jaws’ stereotype, especially species like the great white shark had to suffer from. However, the industry had to face difficulties in integrating conservation ethics with business profitability and tourist satisfaction.

Compared to whale watching tourists, who want to encounter highly charismatic cetaceans in their natural environment, the motivation of tourists seeing sharks is different. To get rid of the stereotype of a man-eating killing machine, people needed to get exposed to sharks as influencing people’s attitudes through wildlife tourism has great potential.

The scenario of Stewart Island can also be seen in South Africa, where the surfing community wants to obtain a ban of the local shark cage diving industry which is claimed to endanger their lives as well as their livelihoods. During their research on a potential condition of white sharks to cage diving boats, Johnson and Kock (2006) wanted to investigate, whether sharks have a reflex to swimmers.

As sharks depend on their smell and vision, Johnson and Kock excluded a conditional response on human activities. A feeding anticipation response, according to the researchers, is less likely to be evoked by a floating shoe as by a cage diving boat. In terms of the visual aspect (containing size, shape and behavior) water users such as scuba divers, swimmers and surfers showed a high dissimilarity compared to fishing and recreational vessels. Fishing vessels can be visited by white sharks as they are simulating chumming vessels in a broader sense.

With regard on the olfactory aspect (containing similarity and strength), human water users showed also a high dissimilarity compared to vessels. Only the spear fisher showed an increased similarity. As a result, an association of human water users with cage diving vessels made by sharks is not given which shows a small overall impact of the cage diving industry on recreation in this area.

However, a real threat are operators who disregard regulations and expose tourists to hazardous situations. This was not the case with the operations in NZ since they were strictly regulated by the Department of Conservation (DoC) and therefore had a very high standard. While spear fisher and paua divers show a similarity, it is unlikely that the waters around Stewart Island will be shark-free, now that cage diving activities will stop. Seal colonies are a main attractor for great white sharks which made the establishment of the ventures possible in the first place. The sharks were there first. And they will probably stick around which means that local residents will be ‘at risk’ at all times.

I think it’s the same problem as with terrestrial predators such as bears and wolves. We’ve always been living with these animals, took their territories through urbanisation and then we’re surprised we encounter them more often. The reason we experience an increase in annual shark attacks is quite simple: Because there are more people in the water! And when there are more paua divers this will naturally increase the risk for an attack. Again, it is more likely to die from a selfie-attempt than a shark bite. But still there seems to be so much misconception around. Even in a country like NZ, where most people grew up with nature.

I think it’s not a surprise that I’m an advocate of respectful wildlife encounters, especially when they’re beneficial to endangered species such a great whites (the conservation biologist comes out again). Me personally, I think the Supreme Court made a wrong decision here. Millions of people come to Aotearoa each year, a big part because of its natural wonders. I came to NZ because worldwide it’s the best place to study marine wildlife tourism. And now the country has lost an important contributor to its marine wildlife tourism portfolio. Because once more a decision was based on emotions rather on science.